This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends Legal

Trends: Takedowns and web-blocks

By Chris Cooke | Published on Wednesday 15 January 2014

2013 was the year when takedown notices and web-blocks seemed to become routine in the music rights sector, with record companies and music publishers now, in the main, resigned to the fact that they have to monitor the web day-to-day to seek and destroy copyright infringing files.

THE TAKEDOWN FRENZY

The system for getting copyright infringing content, or links to it, removed from search engines, blogs, message boards and other user-upload sites originates in American copyright law, even though the rights owners and targeted web platforms are frequently not within the USA.

American law says that the operators of such platforms can circumvent liability for copyright infringement when they inadvertently host or link to infringing stuff as a result of user or automated activity, providing they operate a system through which rights owners can have infringing content or links removed.

But that bit of law puts all the onus of the rights owner to spot the infringing content in the first place and, albeit through precedent set by the American courts, doesn’t set the standards for those takedown systems particularly high.

US content companies have been quietly lobbying in Washington to have both those things changed. But in the meantime, where websites have set up reasonable takedown systems, many rights owners have set about routinely monitoring those sites for infringing files and links, issuing takedown notices when required. Sometimes thousands of them. In one day.

In November, UK record label trade body the BPI, which issues takedown requests on behalf of some of its members, announced it had now issued 50 million such notices to Google alone in the last two and half years.

Meanwhile other labels and publishers are now building their own systems, or more commonly buying in third party technologies, and making web monitoring and takedown issuing a standard part of their rights management activity.

Such work can effectively reduce the amount of illegal copies of any one record on the net, though whether that actually results in better sales or streams elsewhere is debatable. Is it rights management for rights management sake, a cost centre with no real impact on revenue? Well, those now committed to the takedown frenzy don’t seem to think so, and such notices will continue to be issued in ever higher frequencies in 2014.

WEB-BLOCKING

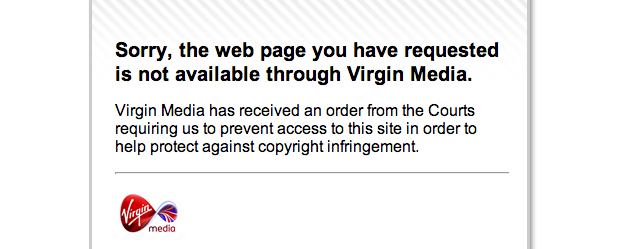

Where websites refuse to respond to takedown notices, the favoured legal action for the music and movie industries in 2013 seemed to be web-blocking.

This process – gaining injunctions that force internet service providers to block access to copyright infringing websites – began for jurisdiction reasons, to overcome two problems: that many such sites are based in countries where its hard to fight infringement through the courts, and even if a piracy operator is found liable for infringement in their home country, it’s relatively easy for them to relocate the operation to another.

With web-blocking, if a rights owner convinces a judge that a site is liable for rampant infringement, it doesn’t matter where that site is based, because the court forces any internet service providers it does have jurisdiction over to stop their customers from accessing the offending website.

The other advantage of web-blocking, rather than the old fashioned approach of trying to sue piracy operations out of business, is that the ISPs – although generally adamant that they won’t block a site without a court order – don’t usually appeal blockade injunctions when they come, making the process relatively speedy, whereas it can take years and years to actually sue a piracy firm into oblivion. And some countries have introduced systems to make the blocking process even speedier.

In the UK, when such a web-blocking system was put to parliament as part of the Digital Economy Act in 2010, it was sidelined in favour of a three-strikes process that targets individual file-sharers rather than the operators of file-sharing sites. But ironically, while the DEA’s three-strikes system is yet to be enacted, the movie and music industries have successfully gained web-blocking injunctions under existing copyright law. And record industry trade body the BPI has now secured numerous web-blocks.

Of course web-blocking is not without its critics, who fear that the principle could be used to shut down websites which may occasionally inadvertently infringe copyrights, but which are basically legitimate operations. Such concerns are stepped up if a web-blocking system is established that cuts out a judicial stage, as will occur in Italy this year when web-block powers are given to electronic communications regulator AGCOM.

Criticism of web-blocking forced US political leaders to abandon plans for such a system there, and – while now common in the UK – web-blocks are yet to be secured in many countries. Though a similar tactic has been employed in some such jurisdictions, by taking a relevant court ruling to a domain registrar – which manages the domains a piracy service uses – and asking them to disable the infringing site’s specific web address, on the basis that the infringement contravenes the registrar’s own terms and conditions. And sometimes it works, resulting in The Pirate Bay switching its main domain several times during 2013.

THE GOOGLE DIMENSION

Of course another point always noted by web-blocking critics is that it’s actually quite easy to circumvent web-blocks, not least because people set up proxy services that redirect users to a blocked site, and those proxies are often very easy to find with a Google search.

Rights owners have secured injunctions to block proxies too, and some web-block court orders make it easy to subsequently add alternative addresses or proxies launched to try and circumvent a blockade. But whenever anything is blocked, it’s usually pretty easy to find an alternative route to the free infringing content within a few days via a search engine.

The music and movie industries would argue that, even if it’s relatively easy to get round a web-block, the fact it makes the process of finding unlicensed content a little more tricky, and alerts users to the fact a site they were using is illegal, is in itself enough to justify proceeding with their web-blocking work.

Although labels and studios would also add that the search engines should be doing their bit to help with the web blocking process. And in much of the world that means Google. Which, although good at complying with takedown requests linked to specific bits of content, has resisted calls to instigate blanket bans against infringing websites. Which means the web giant won’t automatically block any bit of content accessible via The Pirate Bay.

The music industry, of course, has a love-hate relationship with Google. Via YouTube the web-giant provides the music industry with one of its best revenue streams and, ironically, one of the most sophisticated takedown systems. And, of course, through Google Play the web firm operates a download store, streaming service and digital locker.

But on the domain-blocking point the music companies are in conflict with the Google empire.

For its part the web giant says it has changed its search algorithm to favour legit content (the rights owners say it doesn’t work), that the labels and studios need to employ better SEO on their sites to improve their search rankings (the rights owners say they already do), and that the piracy battle should be focused on stopping file-sharing sites from carrying advertising (though some accuse Google’s own ad-network of providing such revenue for some piracy sites).

Interestingly, over Christmas sometimes controversial lyrics website Rap Genius was temporarily pulled from Google search results, though not on copyright grounds, but for breaking the web firm’s own SEO rules.

Expect rights owners to ask this year, if Google can exile sites from its search engine when they break the company’s own laws, why not when sites break the law of the land? Meanwhile keep an eye on a recent French web-block injunction that seemingly forced the search engines as well as ISPs to block the offending sites in the case.