This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends

Trends: Online music piracy – past, present and future

By Chris Cooke | Published on Friday 22 December 2017

The music industry has been much less vocal about piracy in recent years, with the sector’s lobbyists more likely to speak out about the so called ‘safe harbour’ and the otherwise legit websites exploiting what many in the music community see as a loophole in copyright law.

That doesn’t mean piracy went away though. And as the majors slowly start to sign new deals with safe harbour dwellers like SoundCloud, YouTube and even Facebook, perhaps music piracy will become a much bigger talking point again in the next few years.

But what kind of music piracy? CMU Trends reviews developments in online music piracy from the rise of Napster to the new services gaining momentum today.

THE RISE OF ONLINE PIRACY

Music piracy is hardly a new phenomenon. When the UK’s Music Publishers Association was launched in 1881 – long before the emergence of the record industry – the key thing that first brought together competing music publishers around one table was a common desire to tackle the pesky phenomenon of unlicensed sheet music copying.

A century later, in the 1980s, the mantra of a by then fully established record industry was that “home taping is killing music”. For what it’s worth, it didn’t.

However, by the late 1990s the biggest music piracy concern was online. While the music industry was frequently accused of being too slow to recognise the opportunities presented by the rise of the World Wide Web, it was pretty quick to spot the threats.

The emergence of affordable tape-to-tape cassette recorders in the 1980s had further facilitated the aforementioned home-taping phenomenon: where one person legitimately buys an album on cassette, but then illegitimately makes illegal copies of said album onto blank tapes to distribute to friends and family.

The rise of the compact disc made home-taped music much less attractive, while the healthy profit margin on the CD meant a cash-rich record industry was much less likely to worry about all the home-taping that did, nevertheless, continue to occur.

The addition of CD burning functionality to mainstream personal computers – allowing a much superior CD equivalent of home-taping – would have been a cause of great concern, had P2P file-sharing not already been on the horizon by that point.

Although P2P file-sharing was, in essence, the digital equivalent of home-taping, the music industry rightly feared online piracy more. At least home-taping was a time-consuming activity, and the copies made on a tape-to-tape cassette player were never great. And while CD burning had overcome some of those issues, you still had to physically place the illegal copy into another person’s hand.

With P2P file-sharing it was really quick and easy to make the copies. Those copies were of a good quality, and that quality would only improve as internet speeds got faster and higher quality MP3 files could be shared. Crucially, rather than handing out illegally made copies in the playground or workplace, file-sharers could distribute unlicensed music to millions of people across the globe, especially once special P2P file-sharing software, like that provided by Napster and Grokster, started to emerged.

THE BATTLE AGAINST FILE-SHARING

So began the music industry’s long-running battle with P2P file-sharing. From a copyright perspective, when someone makes and distributes a copy of a song or track without permission, that is copyright infringement. The law says that you should sue the infringer for damages. If the infringer infringes on an industrial level and on a commercial basis, there may be a case for criminal proceedings, but the starting point, usually, is that the copyright owner sues the copyright infringer.

The problem with home-taping, CD burning and file-sharing, is that millions of people participate in this kind of piracy. Most of those people infringe copyright for fun rather than profit, and are likely of limited financial means. So even if you can identify the infringer, which is tricky; and even if you could sue millions of people, which you can’t; you only really want to sue rich people, otherwise – even if you win in court – you’re unlikely to see a decent level of damages to make your litigation worthwhile.

So what to do as P2P file-sharing made illegal copying easier and more global? In the early 2000s various measures were proposed.

At this point most music being shared online originated on a CD: could you put software on the disc to stop tracks being ripped or shared? Yes you could. But this might stop the CD from working on a computer, ie the very device on which increasing numbers of consumers want to play their music. Plus anyone with a bit of tech savvy can quickly work out how to circumvent that software, and rip and share your tracks anyway.

Could you sue a few file-sharers, get a load of press around that legal action, and thus provide a deterrent that would stop other file-sharers? Well, you could try. Even though identifying individual file-sharers likely requires legal action against the ISPs before you even get to sue the actual person doing the file-sharing. And even if you do successfully sue a few file-sharers, will that really deter everyone else?

The US record industry went on to sue thousands of people and no one seemed particularly deterred there. Instead the record industry, now busy suing young music fans of limited means, got itself a terrible reputation as a money-grabbing anti-consumer corporate machine, providing file-sharers with a perceived (if dubious) ethical justification for why they were stealing so much music in the first place.

What about the makers of the software; ie the P2P file-sharing clients which were facilitating the file-sharing process? They too were corporate entities, they were much easier to find, and in many cases the people and companies behind that technology – or at least their financial backers – had money to fund decent damages.

A decade of litigation against software companies like Napster, Grokster, Kazaa and LimeWire ensued. Suing those companies required some test cases to set some legal precedents. Were these software makers even liable for copyright infringement? After all, they never actually hosted, copied or distributed any of the unlicensed music, their technology simple connected two individual’s PCs across the internet, so that those two individuals could do the hosting, the copying and the distributing.

Every country has its own copyright regime of course, and quite what each set of copyright law says about file-sharing differs around the world. In some countries it was initially debatable whether even the file-sharers were infringing copyright. As for whether or not the software makers were also liable would depend on the reach of the principle variously known as secondary, contributory or authorising infringement.

This is the principle found in many copyright systems that says that someone who facilitates an infringement may be liable for said infringement, as well as the actual infringer. So, if I own a market and knowingly allow a bootleg CD seller to sell their bootleg CDs, I might also be liable for the bootlegger’s copyright infringement. And I own a market, so I’m presumably worth suing.

Whether or not the makers of P2P file-sharing software were liable for this kind of infringement was initially debatable. The software makers insisted they were not. And they pointed to unsuccessful efforts in the 1980s to hold the makers of tape-to-tape cassette and video recorders liable for contributory infringement.

Those efforts had failed because the makers of the cassette and video recorders successfully argued that their technology had both legitimate and illegitimate uses (because a person could be making copies of their own audio or video), and that once the cassette or video recorder had been sold, the manufacturer of the device had no control over how it was used. The P2P software makers argued that their technology also had legitimate uses, and that they couldn’t control how their software was employed.

For a time, those arguments weren’t entirely dismissed by the courts. Although ultimately, in most jurisdictions, it was eventually ruled that – actually – unlike the maker of a cassette or video recorder, a P2P software maker could control how their technology was used, at least to an extent.

After all, the software maker continued to be directly linked to the users of its technology over the internet, and could monitor how its software was used, or install filters to try to limit the sharing of copyright material without licence. The fact that the P2P software makers didn’t do any of those things made them liable for contributory infringement. And so, slowly but surely, mega-bucks damages were won by the record labels and the P2P networks started to fall down.

Except, as any one P2P software makers went out of business, there was always a new player on the market ready to take its place. Indeed, usually the new P2P service had already taken over before the old service was killed off. And while big business may have been put off investing in the file-sharing game by all this messy litigation, you didn’t need big investment to get a new file-sharing network off the ground.

Meanwhile, file-sharing had evolved. The emergence of BitTorrent technology made file-sharing faster, and resulted in a shift from people using software like Kazaa and LimeWire, over to using BitTorrent-specific search engines like The Pirate Bay and Kickass Torrents. So litigation then followed against the new P2P service providers.

By this point the music industry usually won whenever its cases got to court, but new services continued to pop up, while some – most notably The Pirate Bay – continued to operate despite losing a flurry of lawsuits.

While all this was going on, a whole new wave of file-sharing was occurring where, rather than two file-sharers directly connecting their PCs peer-to-peer, one file-sharer would upload their music collection to a digital locker, share links to that music on a forum, and the other file-sharer would click on those links and download. And so legal action began against the digital lockers and the forum owners.

The digital lockers were actually hosting the copyright infringing material, so – unlike Kazaa and LimeWire – couldn’t use the “but we don’t touch the infringing content” defence. But by this point the tech sector was realising the power of the aforementioned safe harbours that had been inserted into copyright or e-commerce laws in the 1990s.

Providing they had so called ‘takedown systems’ via which copyright owners could demand infringing material be removed, the digital lockers argued they couldn’t be held financially liable for the copyright infringing content they’d been hosting all this time. And, in the main, they were right.

THREE-STRIKES, WEB-BLOCKS AND TAKEDOWN

By the late 2000s precedents had been set in most key jurisdictions that the makers of file-sharing software and the operators of file-sharing hubs and forums were likely liable for contributory infringement, or similar. And a plethora of file-sharing operations had gone offline as a result.

But, as we’ve seen, new file-sharing operations continued to emerge and the file-sharing phenomenon continued. Meanwhile, even though copyright owners were now more confident of victory when they sued file-sharing companies, that didn’t stop that litigation from being costly and time-consuming. All the more so when file-sharing sites deliberately based themselves in less copyright friendly jurisdictions.

To that end, the music industry started to look for other options for fighting online piracy. The two tactics most commonly discussed were three-strikes and web-blocking. The former was a simplified version of the sue-the-fans litigation that the record industry, especially in the US, had tried in the early days of file-sharing. The latter was a simplified version of suing the providers of file-sharing services.

Three-strikes – or ‘graduated response’ – is a system whereby internet service providers send out increasingly stern letters to suspected file-sharers. If the file-sharers ignore those letters, ultimately some sort of sanction occurs, which might be a lawsuit, or a restriction of internet speed, or a suspension or disconnection of internet access.

ISPs never like being forced to police how their customers use the internet. Although in some countries, most notably the US, internet firms did voluntary sign up to an albeit lo-fi version of graduated response. In other countries, most notably France, new anti-piracy laws forced ISPs to participate in this process.

In the UK, the 2010 Digital Economy Act also obliged the net firms to participate in a graduated response system. Though the ISPs managed to put off that participation for years, and only recently did lukewarm warning notes start getting sent out to suspected file-sharers. Which is not what the music industry had anticipated when it successfully negotiated three-strikes into the DEA in 2010.

In the main, web-blocking has been adopted in favour of three-strikes. This is the system whereby a court orders internet service providers to block their customers from accessing specific copyright infringing websites.

In some countries, like the UK, courts have decided they have the power to issue such orders under existing copyright laws. In other countries, like Australia, a bespoke new web-blocking system has been introduced by lawmakers.

Although web-blocks are usually controversial when first introduced in any one country – local ISPs usually moan loudly about copyright owners “censoring the internet” – once web-blocking is up and running the blockades are usually installed without much bother. Indeed, in some countries some internet companies have even started to advocate web-blocking as the most effective anti-piracy tactic.

Web-blocking is an anti-piracy measure of limited effect, given that it is relatively easy for web-users to circumvent the blockades, usually via a simple Google search. Copyright owners recognise this, but feel anything that puts hurdles in the way of piracy sites is a worthwhile endeavour. Although they concurrently wish Google et al would do much more to ensure their search engines aren’t quite so helpful for those looking to access an officially web-blocked site.

But what about those websites that routinely host or link to copyright infringing content but which plead safe harbour protection? Well, assuming the safe harbour defence would stand up in court, the only option left for copyright owners is to push the safe harbour dwelling websites’ takedown systems to the max. Some music companies do just that, issuing a stack of takedown notices against such sites every single day.

Indeed, for some copyright owners, takedown issuing is now just a routine part of rights management, and companies have developed technology to help with the process. Not every takedown system is the same, and so – on top of everything else – the music industry’s lobbyists have had to find time to call for safe harbour regulations to be revised so as to better define what a compliant takedown system should look like.

Slowly but surely some progress has been made in this domain, although even with the best takedown systems the onus is still on the rights owner to spot and request the removal of infringing content, a fact many rights owners resent, even as they issue another flurry of official takedown notices.

STREAM-RIPPING AND BEYOND

As we noted at the start, in more recent years the music industry has been somewhat less vocal on piracy issues. This is partly because legitimate digital music services – in particular subscription streaming – have started to boom and helped take the record industry back into growth after fifteen years of decline. It’s partly because individual rights owners have become much more focused on takedown issuing. It’s partly because of the battle with safe harbour dwelling user-upload sites like YouTube.

However, piracy continues, and just like the legitimate digital music market, it also continues to evolve: from P2P clients to BitTorrent hubs to digital locker linking and so on to stream-ripping. It’s the latter that the music industry’s anti-piracy police have been most focused on of late, with the stream-ripping phenomenon even getting the occasional name-check alongside the customary safe harbour griping.

Stream-ripping allows users to turn a temporary stream into a permanent download, meaning music fans seeking free MP3s no longer need to share files with other fans, they can simply find the track they like on a site like YouTube, run the YouTube link through a streaming-ripping engine, and an MP3 file will quickly start to download. It’s not just YouTube people stream-rip from, although it is a key source for the stream-rippers, as the name of the most famous stream-ripping site – YouTube-mp3 – suggests.

With stream-ripping now high up on the music industry’s anti-piracy agenda, the US record industry began legal proceedings against YouTube-mp3 last year, successfully forcing the service offline in September. However, as with the P2P file-sharing networks of old, as any one stream-ripping service is sued off the internet, there are others eager to take its place. As YouTube-mp3 went offline this autumn, sites like theyoutubemp3.com and mp3juices.cc saw an immediate boost in user numbers. Hence the music companies now looking to lawmakers for help in tackling this latest form of online piracy.

Is stream-ripping already yesterday’s preferred piracy option though? Muso is a London-based company that provides tools for copyright owners to monitor the illegal distribution of their content and issue takedown notices to safe harbour compliant platforms. It also monitors piracy across the entire internet on a daily basis and is constantly looking for the latest trends. Last month its CEO Andy Chatterley shared some of those insights at the Slush Music conference in Helsinki.

He told the Slush Music audience: “In 2016, we tracked 191 billion global visits to piracy platforms, of which 34 billion were related to music. As you can see, piracy remains significant. And remember, those are ‘visits’ – each visit might result in the user accessing an individual track, or a full album, or an entire back catalogue”.

Though, he added, the direction of piracy traffic is constantly evolving. While it’s true that stream-ripping has become increasingly significant in recent years, the big growth in the piracy domain today is actually illegal streaming services that pull in content off the file-sharing networks and then present it to users via a Spotify-type experience.

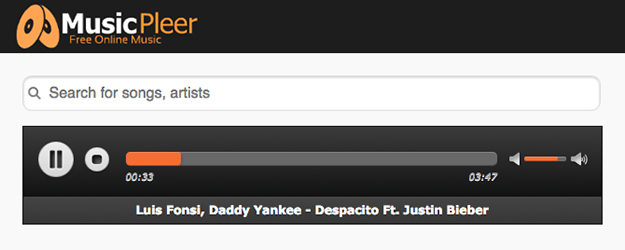

Chatterley: “While 23% of music piracy last year was stream-ripping, our figures show that 40.3% took place on illegal streaming services – platforms like MusicPleer and myzuka.club. Which means that audience behaviour in piracy is mimicking audience behaviour in the legitimate digital music market, ie we are seeing a shift from downloads to streams, and from ownership to access”.

The likes of MusicPleer and myzuka.club are yet to garner much attention within the music industry. Though as more deals are done with the safe harbour dwelling platforms – and if Spotify et al start to see their sign-up rates slow down – it’s these services which might come to dominate the piracy conversation in the years ahead. And while Chatterley notes that none of these illegal streaming platforms are as yet as user-friendly as a legit service like Spotify, they are constantly developing. And becoming more mobile.

“Another way in which piracy is mimicking the legitimate market is the shift to mobile”, says Chatterley. “Last year we saw daily global visits to piracy sites via the user’s computer decline while mobile usage increased. There was an upswing of 66% to mobile devices by December 2016, and this is a trend that we are expecting to see continue”.

Such is the growth of illegal streaming services, it may be that the music industry’s old piracy foes that are based around unlicensed downloads go into terminal decline on their own accord. After all, there is a generation coming through for whom the concept of owning music is alien.

True, this generation wants ‘offline’ listening, and that requires a download, but these fans aren’t aiming to gather an MP3 collection of their own. Which will make BitTorrent file-sharing, digital locker link clicking and all that stream-ripping seem very old fashioned indeed.

So, the battle against music piracy enters yet another new phase, in which the reach of current copyright laws will need to be tested once again and new anti-piracy rules may need to be lobbied for. Of course, if the streaming boom goes on, and the record industry continues to grow, the piracy problem may feel less pressing. Just like the CD boom stopped everyone worrying about home taping.

Anti-piracy efforts will continue, but not because anyone is foolish enough to believe piracy will ever be stopped. More because rights owners continue to believe that – at the same time as making legit music services as magnificent as possible – it’s important to make accessing illegal platforms as terribly tedious as it can be.

Meanwhile, Chatterley reckons there is another reason for keeping an eye on the piracy platforms. Because in amongst all that illegal distribution of content across the internet is yet more valuable data.

“A big part of the Muso service is content protection and, with piracy as prevalent as ever, it’s important rights owners continue being active in this space”, he says.

“But”, he adds, “we also believe there is a massive opportunity in understanding the behaviour of the piracy audience and analysing the data we can pull out of the piracy platforms – on a title level, a genre level and a country level – so to provide ever better business intelligence. Using this data, alongside other sales data, you get to see a bigger picture of music consumption and audience behaviour. Muso’s data platforms enables right-holders and other interested parties to do just that, to see the bigger picture”.