This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Business News Labels & Publishers Legal Top Stories

New York appeals court decides there isn’t a performing right on golden oldie recordings after all

By Chris Cooke | Published on Wednesday 21 December 2016

If you thought that the radio royalty element of the good old pre-1972 copyright debate in the US was all over, think again. An appeals court in New York has decided that satellite broadcaster Sirius XM doesn’t have to pay royalties to artists and labels when it plays 1960s recordings.

Members of the Copyright Technicality Fan Club will recall that this all stems from the fact US-wide federal copyright law only protects sound recordings released since 1972, with older tracks getting their protection from state-level copyright law.

Meanwhile US copyright law is unusual in that there is no general ‘performing right’ as part of the sound recording copyright. So whereas elsewhere in the world AM/FM radio stations that play music need licences from both labels and music publishers (covering, respectively, recording and song copyrights), in the US broadcasters only need the latter. Except online and satellite broadcasters, because federal copyright law does provide a ‘digital performing right’ to sound recording owners.

But what about those often quite dated state copyright laws? They are often ambiguous about performing rights and sound recordings, but certainly don’t include any specific rules about online and satellite stations. Meanwhile, AM/FM stations have never paid royalties to labels for the records they play, however old the tracks may be. To that end both Sirius and Pandora decided that, while they must pay royalties to labels and artists for post-1972 catalogue, when they play older tracks no royalties are due.

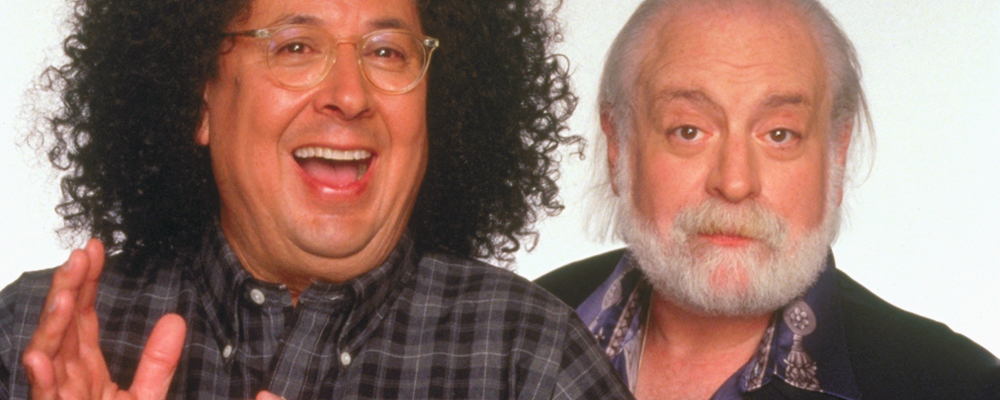

But some in the artist and label community reckoned that royalties should be paid on those older tracks. Flo & Eddie – former members of ‘Happy Together’ band The Turtles – went legal on the matter, launching litigation in three states and arguing that there was, in fact, a performing right for sound recordings in state level copyright law.

Though given state laws make no distinction between AM/FM and satellite/online radio services, that would mean traditional radio stations should have been paying royalties to labels whenever they played golden oldies all these years, which they had not.

Nevertheless, when the matter reached the Californian courts, Flo & Eddie won, setting a landmark precedent that led to multi-million dollar settlements between the record industry and Sirius and Pandora, and just last month between Sirius and Flo & Eddie.

The duo initially enjoyed success on the issue in the New York courts too, where one judge specifically pondered whether the fact the labels had never demanded royalties from traditional radio stations for playing 1960s tracks implied there was, in fact, no sound recording performing right under the state’s copyright system. But that judge decided that the failure by the labels to claim royalties shouldn’t make any difference.

However, Sirius appealed the New York case, and an appeals court there yesterday reached a different conclusion on that last point. It would be “illogical”, said one appeals judge, to decide that a performing right had been lingering there in New York copyright law all these decades yet no rights owner or court had ever sought to enforce it. Illogical I tell you! And judge Leslie Stein even sneaked a little joke into her ruling, so she must be right.

“It would be illogical to conclude that the right of public performance would have existed for decades without the courts recognising such a right as a matter of state common law, and in the absence of any artist or record company attempting to enforce that right in this state until now”, wrote Stein.

She added that she agreed with legal reps for Sirius that there was a “broad understanding” in both federal and state law that the sound recording copyright does not include a general performing right.

And that’s because artists and labels get lots of lovely promotion when their music is played on the radio, so shouldn’t be paid for it too – that being the US radio industry’s longtime argument as to why they shouldn’t give cash to the labels. And just because slumping record sales possibly lower the value of all that free promo, that’s no reason for judges to infer a new right for the labels, the judge went on.

“Common sense supports the explanation”, she wrote, “that the record companies and artists had a symbiotic relationship with radio stations, and wanted them to play their records to encourage name recognition and corresponding album sales”. And, she continued – oh, and by the way, the joke’s coming up, “those participants have co-existed for many years and, until now, were apparently ‘happy together’”. Ha, ha! Happy together! See. That’s Flo & Eddie’s most famous hit. Good times. Yeah, OK, I oversold it slightly by saying there was a joke in here. Sorry.

“While changing technology may have rendered it more challenging for the record companies and performing artists to profit from the sale of recordings”, she continued, “these changes, alone, do not now warrant the precipitous creation of a common law right that has not previously existed. Simply stated, New York’s common law copyright has never recognised a right of public performance for pre-1972 sound recordings. Because the consequences of doing so could be extensive and far-reaching, and there are many competing interests at stake, which we are not equipped to address, we decline to create such a right for the first time now”.

One of the far-reaching consequences with inferring a general performing right for pre-1972 sound recordings is that AM/FM stations could be sued back into the dim and distant past for playing 1960s tracks without licence. Indeed music firm ABS Entertainment launched such a case against CBS last year, the media firm having to employ a technicality that even the CTFC’s most ardent members felt was a little bit cheeky: that CBS stations played remastered versions of golden oldies, and the remastering reset the copyright at a point sometime after 1972.

A total of six judges considered the appeal in the New York Flo & Eddie dispute, with four siding with Sirius. Though one of the other judges who concluded there wasn’t a general performing right for pre-1972 sound recordings was keen to state that that didn’t mean on-demand streaming services could side-step paying royalties to the labels on golden oldies as well.

Technically a stream requires making a copy anyway – so even without a state-level general performing right or a federal-level digital performing right, Spotify and Apple Music would still require a licence from the labels. Though you could say that, technically speaking, personalised radio services are also making copies in the delivery of a stream, yet in the US it has generally been agreed that Pandora et al are only exploiting the (digital) performing rights of the copyright.

But anyway, the big question now is what does this mean for Sirius, Pandora, the record labels, and any heritage artists who joined Flo & Eddie’s class action?

The settlement between Sirius and Flo & Eddie acknowledged that the duo’s court cases in New York and Florida were still subject to appeal, and the size of the damages settlement agreed was dependent on the outcome of those cases. It’s not clear if this new ruling has any impact on the separate settlements between Sirius, Pandora and the major record companies.

Meanwhile, moving forward, if California says there is a performing right for recordings in its copyright laws but New York says there is not in theirs, it could mean that label royalties have to be paid in some states but not others. It’s not clear what the technical and constitutional implications of that would be.

Of course, another argument the music industry could use here is that it’s a bit mad for key elements of federal copyright law – like the digital performing right – to not apply to recordings protected under state laws, and that federal copyright rules of this kind should be applied across the board.

The music companies weren’t originally so keen on that argument though, because they were concurrently trying to argue that the safe harbours – which they hate so much and which also come from federal law – shouldn’t apply on pre-1972 recordings. The record industry lost that argument, though is currently trying to get the US Supreme Court to review that judgment, so probably doesn’t want to start shouting about the key principles of federal copyright law being applied to older sound recordings just yet.

Meanwhile, with the likes of Pandora entering into wider deals with the record companies in order to launch fully on-demand streaming services, it could be that issues like this can be settled within those agreements. But that doesn’t necessarily help the likes of Sirius. So, maybe there is more lobbying and litigation to come before we can all be genuinely happy together. Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha! Merry Christmas everybody!